One Quaker's View on:

The Power of a smile. By Jan Marsh

A Friend has his baby grandson (and parents of course) staying and we got talking about the wonderful feelings a baby creates in us, and in particular how we can't resist smiling back when a baby smiles.

It got me thinking about how this works, within us and between us.

On a sunny spring day I walk down town and suddenly people in the street are smiling at me. I must be going around with a happy grin on my face and they respond. That makes me smile even more broadly. Neuroscience tells us that the good feeling when someone smiles at us comes not just from their friendliness, which of course is nice, but from the effect of our own smile on ourselves.

Does it strike you as strange to think of that? It's a feedback loop created by the vagus nerve, the longest of the cranial nerves, which forms a circuit linking the brain to the heart, lungs, diaphragm and gut. It's called the vagus nerve, from the same Latin root as 'vagabond', because it wanders through the body and it is responsible for a wide range of functions which scientists are only now beginning to understand. It's a major part of the parasympathetic 'rest and digest' nervous system which regulates heart rate, blood pressure, breathing and digestion.

When a car fails to stop for us on the pedestrian crossing or we get angry at the boss's email or argue with our partner, our ever-vigilant sympathetic nervous system revs up the 'fight or flight' response which acts as though a tiger has leapt out of the bushes. Once we assess that it's not a tiger, the vagus nerve settles us down via the parasympathetic system, sending messages through its tendrils into many different organs so that enzymes and proteins flow out to calm us. Its direct connection between gut and brain is constantly monitoring and updating our status to keep us on an even keel.

The vagus nerve responds to calm and safety. It can be stimulated in many ways: deep breathing, a neck massage, cool water on our face, time with friends, laughter.

This is where the smile comes in. The eye crinkles of a genuine smile signal to the brain that all is well. As the vagus nerve takes up the message, a cascade of subtle changes runs through our organs and our system is calmed and regulated. Others pick up the positive emotion and respond to it. Just think how irrestistible the smile of a baby is – we smile back even at stranger's babies in the street and often their mothers smile at us too. Think of those smiles being passed around and all those vagus nerves practically purring!

Winter - a tough time for a fair weather friend. By Jan Marsh

Classic Quaker View. Reprinted & slightly revised!

I'm a fair weather friend – I always feel better on a sunny day. Winter can be tough, with the cold weather and short days keeping me indoors too much. The garden lies dormant so there is little to do there and no motivation to be out in a chill wind.

Our winters are not really that hard. A few frosts, snow on the mountains across the bay, a cold wind blowing up from Antarctica some days and sometimes grey, rainy stretches. Most days we will see the sun – cheerful, even if not very warm. But for many years I got a bit depressed during the winter, especially when I was at work full-time, leaving the house in darkness and returning in darkness. I felt very shut in and badly needed the walk I regularly took at lunchtime to get a coffee and spend a few minutes reading the paper in a cafe, just to feel connected to the outside world.

Fortunately, my love of swimming gives me an all-weather form of exercise although I do miss the outdoor pool where I swim during the summer, often with a 50 metre lane all to myself. At summer's end, I have to adjust to the crowds at the indoor pool but I still love to swim and make sure I do so three times a week. I also have a few hardy friends who will walk in most weathers, so I fit in a social walk at least once a week, often with a cup of coffee to follow. I'm happy to walk by myself too, especially if I can take advantage of a sunny hour now and then. And since my friend and coach taught me to run 'injury-free' as he put it, I aim to run once a week. That's not really often enough to improve but I still enjoy it. That's the exercise taken care of and I'm sure it helps a lot in getting through the winter.

I've also learned to plan for the long periods of time indoors. I have friends who are keen knitters so I took some advice from them and picked up a skill I had hardly used since I was a child. My first project was a patchwork rug for my grandson, a task shared with my daughter, sisters and mother. We all made some squares which I stitched together and my sister knitted an edging around it. We were pleased with the result and he still has it. After that I went on to cot blankets which I donated to the young parents' school, a place for parents and their babies to continue their education in a classroom near where I live. I added a few beanies and hoped they would be good for the little ones. Now I'm back to knitting for the next grandchildren.

There's something very calming about listening to the radio or some music while creating something stitich by stitch. I had to get over the idea that it's an occupation for elderly people – or accept that I am a little elderly! - and now I am glad I revived the skill.

Guilt-free TV goes well with winter too. I have my Netflix subscription and I can choose a series to look forward to in the evening. With the heating on and the cat on my lap, perhaps a cosy rug over my shoulders, it feels a little like the Danish hygge which is such a good example of how to pass the winter. Of course, stretching out on the couch with a book is always a good option, too and hot chocolate never goes amiss.

I'm pleased at how well I'm getting through winter. The buds are on the trees before you know it!

Silence by Scott Russell Sanders

from Falling Towards Grace: Images of Religion and Culture from the Heartland, J. Kent Calder, ed. 1998

Finding a traditional Quaker Meeting in Indianapolis would not be easy. No steeple would loom above the meeting house. no bell tower, no neon cross. No billboard out front would name the Preacher or proclaim the sermon topic or tell sinners how to save their souls. No crowd of nattily dressed churchgoers would stream towards the entrance from a vast parking lot filled with late model cars. No bleat and moan of organ would roll from the sanctuary doors.

I know all that from having worshipped with Quakers off and on for 30 years., beginning when I was a graduate student in England. They are a people who call so little attention to themselves or their gathering places as to be nearly invisible. Yet when I happened to be in Indianapolis one Sunday this past January, I still set out in search of the meeting house without street address or map. My search was not made any easier by the snow billowing down on the city that morning. I recall hearing that the North Meadow Circle of Friends gathers in a house near the intersection of Meridian and 16th Streets, a spot I found easily enough. Although I could not miss the imposing Catholic Center nearby on Meridian nor the Joy of All Who Sorrow Eastern Orthodox Chruch just a block away on 16th, the only landmark at the intersection itself was the International House of Pancakes. Figuring somebody in there might be able to direct me to the Quakers, I went inside, where I was greeted by the smell of sasusages and the frazzled gaze of the hostess. No, she'd never heard of any Quakers.

“But there's the phone book", she told me, gesturing with a sheaf of menus. “You're welcome to look them up." I thanked her, and started with the Yellow Pages. No luck under “Churches". Nothing under “Religion". Nothing under “Quakers" or “Friends, Society of". Finally, in the white pages, I found a listing for the North Meadow Circle, with a street address just a couple of blocks away. As I returned the phone book to its cubbyhole, I glanced across the room, where a throng of diners tucked into heaping platters of food, and I saw through the plate-glass window a man slouching past on the sidewalk. He wore a hat encrusted with leaves, a jacket torn at the elbows to reveal several dingy layers of cloth underneath, baggy trousers held up with a belt of rope, and broken leather shoes wrapped with silver duct tape. His face was the color of dust. He was carrying a bulging gray sack over his shoulder, like a grim Santa Claus. Pausing at a trash can, he bent down to retrieve something, stuffed the prize in his bag, then shuffled north on Meridian into the slant of snow.

I thought how odd it was that none of the diners rushed out to drag him from the street into the House of Pancakes for a hot meal. Then again, I didn't rush out either. I only stood there feeling pangs of guilt, an ache as familiar as heartburn. What held me back? Wouldn't the Jesus whom I try to follow in my own muddled way have chosen to feed that man instead of searching for a prayer meeting? I puzzled over this as I drove the few blocks to Talbot Street, on the lookout for number 1710, the address I had turned up in the phone book. The root of all my reasons for neglecting that homeless man, I decided, was fear. He might be crazy, might be strung out, might be dangerous. He would almost certainly have problems greater than I could solve. And there were so many more like him, huddled out front of missions or curled up in doorways all over Indianapolis this bitterly cold morning. If I fed one person, why not two? Why not twenty? Once I acknowledged the human need rising around me, what would keep me from drowning in all that hurt?

A whirl of guilt and snow blinded me to number 1710, even though I cruised up and down that stretch of Talbot Street three times. I did notice that the neighbourhood was in transition, with some houses boarded up and others newly spiffed up. A few of the homes were small enough for single families, but most were big frame duplexes trimmed in fretwork and painted in pastels, or low brick apartment buildings that looked damp and dark and cheap. On my third pass along Talbot I saw a portly man with a bundle of papers clamped under one arm turning in at the gate of a gray clapboard house. I rolled down my window to ask if he knew where the Friends worshipped, and he answered with a smile, “Right here."

I parked next door in a lot belonging to the Herron School of Art. As I climed out of the car, a pinwheel of pigeons lifted from the roof of the school and spun across the sky, a swirl of silver against pewter clouds. No artists appeared to be up and about this early on a Sunday, but some of their handiwork was on display in the yard, including a flutter of cloth strips dangling from wire strung between posts, an affair that looked, under the weight of snow, like bedraggled laundry. An inch or two of snow covered the parking lot, and more was falling. Footprints scuttled away from the five or six cars, converged on the sidewalk, then led up to the gate where I had seen the man carrying the bundle of papers. True to form, the Quakers had mounted no sign on the brick gateposts, none on the iron fence, none on the lawn. Twin wreaths tied with red ribbons flanked the porch, and a wind-chime swayed over the front steps. Only when I climbed onto the porch did I see a small painted board next to the door, announcing an “Unprogrammed (Silent) Meeting" is held here every First Day at 10am, and that “Each person's presence is reason to celebrate."

There was celebration in the face of the woman who greeted me at the door. “So good to see you," she whispered. “Have you worshipped with Quakers before?" I answered with a nod. “Wonderful," she murmered, pointing the way: “We're right in there."

I walked over the creaking floorboards from the narrow entrance hall into a living room cluttered with bookshelves, cozy chairs, and exuberant plants. Stacks of pamphlets filled the mantle above a red brick fireplace. Posters on the wall proclaimed various Quaker testimonies, including opposition to the death penalty and a vow against war. It was altogether a busy, frowsy, good-natured space.

From there I entered the former dining room, which had become the meeting room, and I took my seat on a wooden bench near the bay windows. Five other benches were ranged about, facing one another, to form an open square. Before closing my eyes, I noticed I was the ninth person to arrive. No one spoke. For a long while the only sounds were the scritch of floorboards announcing latecomers, the sniffles and coughs from winter colds, the rumble and whoosh of the furnace, the calling of doves and finches from the eaves. The silence grew so deep that I could hear the blood beating in my ears. I tensed the muscles in my legs, hailed up my fists, then let them relax. I tried stilling my thoughts, tried hushing my own inner dialogue, in hopes of hearing the voice of God.

That brazen expectation, which grips me now and again, is a steady article of faith for Quakers. They recite no creed, and they have little use for theology, but they do believe that every person may experience direct contact with God. They also believe we are most likely to achieve that contact in stillness, either alone or in the gathered meeting, which is why they use no ministers or music, no readings or formal prayers, no script at all, but merely wait in silence for inward promptings. Quakers are mystics, in other words, but homely and practical ones, less concerned with escaping to heaven than with living responsibly on earth. The pattern was set in the seventeenth century by their founder, George Fox, who journeyed around England amid civil and ecclesiastical wars, searching for true religion. He did not find it in catherdrals or churches, did not hear it from the lips of priests, did not discover it in art or books. Near despair, he finally encountered what he was seeking within his own depths: “When all my hopes in all men were gone, so that I had nothing outwardly to help me, nor could I tell what to do, then, oh then, I heard a voice which said, 'There is one, even Christ Jesus that can speak to thy condition,' and when I heard it my heart did leap for joy."

My heart was too heavy for leaping, weighed down by thoughts of the unmet miseries all around me. The homeless man shuffled past the House of Pancakes with his trash bag, right down the main street of my brain. I leaned forward on the bench, elbows on knees, listening. By and by there came a flurry of sirens from Meridian, and the sudden ruckus made me twitch. I opened my eyes and took in more of the room. There were twelve of us now, eight women and four men, ranging in age from 20 or so to upwards of seventy. No suits or ties, no shirts, no lipstick or mascara. Instead of dress-up clothes, the Friends wore jeans or wool shirts in earth colors, jeans and corduroys, boots or running shoes or sandals with wool socks. The wooden benches buffed and scarred from long use, were cushionless except for a few rectangles of carpet, only one of which was claimed. A pair of toy metal cars lay nose-to-nose on one bench, a baby's bib and a Bible lay on another, and here and there were boxes of Kleenex. Except for those few objects, and the benches and people, the room was bare. There was no crucifix hanging on the walls, no saint's portrait, no tapestry, no decoration whatsoever. The only relief from the white paint were three raise-panel doors that led into closets or other rooms. The only movement, aside from an occasional shifting of hands or legs, was the sashay of lace curtains beside the bay windows when the furnace blew, and those windows also provided the only light.

To anyone glancing in from outside, we would have offered a dull spectacle: a dozen grown people sitting on benches, hands clasped or lying open on knees, eyes closed, bodies upright or hunched over, utterly quiet. “And your strength is, to stand still," Fox wrote in one of his epistles, “that ye may receive refreshings; that ye may know how to wait, and how to walk before God, by the Spirit of God within you." When the refreshing comes, when the Spirit stirs within, one is supposed to rise in the meeting and proclaim what God has whispered or roared. It might be a prayer, a few lines from the Bible or another holy book, a testimony about suffering in the world, a moral concern, or a vision. If the words are truly spoken, they are understood to flow not from the person but from the divine source that upholds and unites all of Creation.

In the early days, when hundreds and then thousands of people harkened to the message of George Fox as he traveled through England, there was often so much fervent speaking in the meetings for worship, so much shaking and shouting under the pressure of the Spirit, that hostile observers mocked those trembling Christians by calling them “Quakers." The humble followers of Fox, indifferent to the world's judgement, accepted the name. They also called themselves Seekers, Children of the Light, Friends in the Truth, and, eventually, the Society of Friends. Most of these names, along with much of their religious philosophy, derived from the Gospel according to John. There in the first chapter of the recently translated King James version they could read that Jesus “was the true Light, which lighteth every man that cometh into the world." In the fifteenth chapter they could read Christ's assurance to his followers: “Henceforth I call you not servants; for the servant knoweth not what his lord doeth: but I have called you Friends; for all things that I have heard of my Father I have made known unto you."

There was no outward sign of fervor on the morning of my visit to the North Meadow Circle of Friends. I sneezed once, and that was the loudest noise in the room for a long while. In the early years, meetings might go on for half a day, but in our less-patient era they usually last about an hour. There is no set ending time. Instead one of the elders, sensing when the silence has done its work, will signal the conclusion by shaking hands with a neighbor. Without looking at my watch, I guessed that most of an hour had passed, and still no one had spoken.

It would have been rare in Fox's day for an entire meeting to pass without any vocal ministry as the Quakers call it. But it is not rare in our own time, judging from my reading and from my visits to meetings around the country. Indeed, Quaker historians acknowledge that over the past three centuries the Society has experienced a gradual decline in spiritual energy, broken by occasional periods of revival, and graced by many vigorous, God-centered individuals. Quakerism itself arose in reaction to a lacklustre Church of England, just as the Protestant Reformation challenged a corrupt and listless Catholic Church, just as Jesus challenged the hide-bound Judaism of his day. It seems to be the fate of religious movements to lose energy over time, as direct encounters with the Spirit give way to secondhand rituals and creeds, as prohpets give way to priests, as living insight hardens into words and glass and stone.

The Quakers have resisted this fate better than most, but they have not escaped it entirely. Last century, when groups of disgruntled Friends despaired what they took to be a moribund Society, they split off to form congregations that would eventually hire ministers, sing hymns, read scriptures aloud, and behave for all the world like other low-temperature Protestant churches. In mid-western states such as Indiana, in fact, these so-called "programmed" Quaker churches have come to outnumber the traditional silent meetings.

I could have gone to a Friends church in Indianapolis that Sunday morning, but I was in no mood to sit through anybody's programme, no matter how artful or uplifting it might be. What I craved was silence - not absolute silence, for I welcomed the ruckus of doves and finches, but rather the absence of human noise. I spend nearly all my waking hours immersed in language, bound to machines, following streets, obeying schedules, seeing and hearing and touching only what my clever species has made. I often yearn, as I did that morning, to withdraw from all our schemes and formulas, to escape from the obsessive human story, to step out of my own small self and meet the great Self, the nameless mystery at the core of being. I had a better chance of doing that here among the silent Quakers, I felt, than anywhere else I might have gone.

A chance is not a guarantee of course. I had spent hundreds of hours in Quaker meetings over the years, and only rarely had I felt myself dissolved away into the Light. More often I had sat on hard benches rummaging through my past, counting my breaths, worrying about chores, reciting verses in my head, thinking about the pleasures and evils of the day, half hoping and half fearing that some voice not my own would break through to command my attention. It is no wonder that most religions put on a show, anything to fence in the wandering mind and fence out the terror. It's no wonder that only a dozen people would seek out this Quaker meeting on a Sunday morning, while tens of thousands of people were sitting through a scripted performances in other churches across Indianapolis.

Carrying on one's own spiritual search, without maps or guide, can be scary. When I sink into meditation, I often remember the words of Pascal: “the eternal silence of these infinite spaces fills me with dread." What I take him to mean is that the universe is bewilderingly large and enigmatic; it does not speak to us in any clear way; and yet we feel, in our brief spell of life, an urgent desire to learn where we are and why we are and who we are. The silence reminds us that we may well be all on our own in a universe empty of meaning, each of us an accidental bundle of molecules, forever cut off from the truth. If that is roughly what Pascal meant, then I suspect that most people who have thought much about our condition would share his dread. Why else do we surround ourselves with so much noise? We plug in, tune in, cruise around, talk, read, run, as though determined to drown out the terrifying silence of those infinite spaces.

A car in need of a muffler roared down Talbott Street past the meeting house, and the racket hauled me back to the surface of my mind. Only when I surfaced did I realize how far down I had dived. Had I reached bottom? Was there a bottom at all, if so, was it only the floor of my private psyche, or was it the ground of being?

As I pondered, someone stood heavily from a bench across the room from me. Although Quakers are not supposed to care who speaks, I opened my eyes, squinting against the somber snowlight. The one standing was the portly man who I had asked the way to the meeting house. A ruff of pearly-gray hair fell to his shoulders, a row of pens weighted the breast pocket of his shirt, and the cuffs of his jeans were neatly rolled. He cleared his throat. In times of prayer, he said, he often feels overwhelmed by a sense of the violence and cruelty and waste in the world. Everywhere he looks he sees more grief. When he complains to God that he's fed up with problems and would like some solutions for a change, God answers that the solutions are for humans to devise. If we make our best effort, God will help. But God isn't going to do the work for us. We are called not to save the world but to carry on the work of love.

All this was said intimately, affectionately, in the tone of a person reporting a conversation with a close friend. Having uttered his few words, the speaker sat down. The silence flowed back over us. A few minutes later, he grasped the hand of the woman sitting next to him, and with a rustle of limbs greetings were exchanged all around the room. We blinked at one another: returned from wherever it was we had gone together, separated once more into our twelve bodies. Refreshed I took up the sack myself, which seemed lighter than when I had carried it into this room. I looked about, gazing with tenderness at each face, even though I was a stranger to all of them

A guest book was passed around for signatures. The only visitor beside myself was a man freshly arrived from Louisiana, who laughed about needing to buy a heavier coat for this Yankee weather. An elder mentioned that donations could be placed in a small box on the mantle, if anyone felt moved to contribute. People rose to announce social concerns and upcoming events. An hour and a half of nearly unbroken silence, suddenly the air filled with talk. It was as though someone had released into our midst an aviary's worth of birds.

Following their custom, the Friends took turns introducing themselves and recounting some news worthy event from the past week. A woman told of lunching with her daughter-in-law, trying to overcome some hard feelings, and about spilling a milkshake in the midst of the meal. A man told how his son's high school basketball coach took the boy out of the game for being too polite toward the opponents. The father jokingly advised his son to scowl and threaten, like the professional athletes whom the coach evidently wished for him to emulate. This prompted a woman to remark that her colleagues at work sometimes complained that she was too honest: “Lie a little, they tell me. It greases the wheels." The only student in the group, a young woman with a face as clear as spring water, told of an assigment that required her to write about losing a friend. “And I've spent the whole week in memory," she said. A man reported on his children's troubled move to a new school. A woman told of her conversation with a prisoner on death row. Another told of meeting with a union organiser while visiting Mexico. “They are so poor," she said,“we can't even imagine how poor." A woman explained that she and her husband, who cared nothing for football, would watch the Super Bowl that afternoon, because the husband's estranged son from an earlier marraige was playing for the Green Bay Packers. When my turn came, I described hiking one afternoon that week with my daughter Eva, how we studied the snow for animal tracks, how her voice lit up the woods. Others spoke about cleaning house, going to a concert, losing a job, caring for grandchildren, suffering pain, hearing a crucial story: small griefs, small celebrations.

After all twelve of us had spoken, we sat for one final moment in silence, to mark an end to our time together. Then we rose from those unforgiving benches, pulled on coats, and said our goodbyes. On my way to the door, I was approached by several Friends who urged me to come again, and I thanked them for their company.

As I walked outside into the sharp wind, I recalled how George Fox had urged his followers to “walk cheerfully over the world, answering that of God in every one." There were still no footprints leading to the doors of the art school, no lights burning in the studios. I brushed snow from the windows of my car with gloved hands. To go home, I should have turned south on Meridian, but instead I turned north. I drove slowly, peering into alleys and doorways, looking for the man in the torn jacket with the bulging gray sack over his shoulder. I never saw him, and I don't know what I would have done if I had seen him. Give him a few dollars? Offer him a meal at the International House of Pancakes? Take him home?

Eventually I turned around and headed south, right through the heart of Indianapolis. In spite of the snow, traffic was picking up, for the stores recognised no Sabbath. I thought of the eighteenth century Quaker, John Woolman, who gave up shopkeeping and worked modestly as a tailor, so that he would have time for seeking and serving God. “So great is the hurry in the spirit of this world," he wrote in 1772, “that in aiming to do business quickly and to gain wealth the creation of this day doth loudly groan." In my Quakerly mood, much of what I saw in the capital was distressing - the trash on the curbs, the bars and girlie clubs, the war memorials, the sheer weight of buildings, the smear of pavement, the shop windows filled with trinkets, the homeless men and women plodding along through the snow, the endless ads. I had forgotten that today was Super Bowl Sunday until the woman at meeting spoke of it, and now I could see that half the billboards and marquees and window displays in the city referred to this national festival, a day set aside for devotion by more people, and with more fervor, than any date on the Christian calendar.

“The whole mechanism of modern life is geared for a flight from God," wrote Thomas Merton. I have certainly found it so. The hectic activity imposed on us by jobs and families and avocations and amusements, the accelerating pace of technology, the flood of information, the proliferation of noise, all combine to keep us from that inward stillness where meaning is to be found. How can we grasp the nature of things, how can we lead gathered lives, if we are forever dashing about like water-striders on the moving surface of a creek?

By the time I reached the highway outside of Indianapolis, snow was falling steadily and blowing lustily, whiting out the way ahead. Headlights did no good. I should have pulled over until the sky cleared, like a sensible fellow. But the snow held me. I lost all sense of motion, lost awareness of road and car. I seemed to be flaoting in the whirl of flakes, caught up in the silence, alone yet not alone, as though I had slipped by accident into the state that a medieval mystic had called the cloud of unknowing. Memory fled, words flew away, and there was only the brightness, here and everywhere.

Hatred: "ATime to Hate" by Philip Gulley,

from For Everything a Season: Simple Musings on Living Well.

Philip Gully first became acquainted with Quakers at the age of twenty when he began attending Plainfield Friends Meeting in west central Indiana, USA. This Meeting is in the programmed tradition, which employs pastors, and he became a pastor. Gulley has published twenty eight books. Perhaps his most famous is 1997's Front Porch Tales. For Everything a Season from which this essay comes was published in 1999. He published Living the Quaker Way in 2015. His essay, "A Time to Hate" addresses the Quaker testimony against doing violence against others.

"When I was a teenager and became a Quaker, the pastor called to tell me someone from the church would be appointed to teach me the faith.

I was hoping they would send an alluring girl to be my mentor, a beauty who would sit on the couch beside me and, over the course on many evenings, instruct me in the Christian life. Instead, they sent Carolyn Kellum, who was in her late sixties and a pacifist - the first pacifist I had ever met. Such a novelty! She almost made me forget about teenage girls. Almost.

Everyone I knew said things like. "Of course I don't like war, but . . ." then would name the circumstances in which a Christian might hate someone enough to shoot him dead. Carolyn told me point blank that Christians were commanded to love, not hate, their enemies. Case closed.

"Don't you believe those preachers who tell you it is possible to love your enemy and still kill them. It can't be done.", she said.

That was thwenty years ago, and ever since then I've been trying to find a way to hate certain people and still walk close to Jesus, but without success. If you've found a way to do that, let me know. There are several people I would love to hate if I thought I could get away with it.

As long as I can remember I've been trying to figure out what it means to be grown up. My older son is six years old. When I was his age, I thought being grown-up came with age. Of course, that isn't true. We all know people who are in their fifties and haven't grown up.

When my Grandma Norma was a little girl, she thought a grown-up was someone who could eat icecream whenever he or she wanted.

When I was as teeanger, I thought a grown-up was someone who had sex. I suspect a lot of teenagers think that, which is why so many of them experiemnt with sex. It took me several years, and much pain, to learn that grown-ups don't allow their hormones to make those decisions best left to the brain.

When I graduated from high school, I thought grown-ups were people who got jobs and supported themselves. I was partially right. Of course, being grown-up means much more than taking care of yourself, but it's a good start. There are some people who never get that far.

When I married my wife and we started a family, I thought a grown-up was someone who took good care of not only himself but also his family. Someone who could lay aside personal gratification for the good of another. Someone who chose staying home over bar-hopping, who went to the PTA meeting instead of staying home to watch the game. That is a big part of what it means to be grown-up - the ability to care for others as well as the self, to lay aside personal desires for the good of someone you love. But that is not all.

There is more.

Ultimately, to be grown-up means that wisdom, reason, and love dictate our choices, as opposed to emotions, lusts, and urges.

For example, people who commit adultery or who sacrifice their families on the altar of their careers have surrendered to emotions, lusts, and urges. They have failed to make important decisions based on wisdom, reason, and love. They live as children, not as adults.

If we allow ourselves to hate other persons and make choices on the basis of hate, rather than on the basis of wisdom, reason, and love, we are not grown-up. For we are allowing our emotions and urges to dictate our actions. Grown-ups don't do that; children do.

A big problem in our world today is that many grown-ups haven't grown up. Their life choices are driven by emotions, lusts and urges, unchecked by any sense of morality, reason, or wisdom. Tney lust without reserve. They satisfy every material longing. They neglect those who count on them. They give hate free rein in their lives. Consequently, they have not grown-up. They walk around in adult bodies. They are entrusted with adult responsibilities. But they ultimately bring ruination to themselves and others because their life choices are driven by the wrong forces.

Now I want to tell you a lie. Hate is an emotion we can't help. Hate is a feeling we cannot overcome. If we hate someone, it is because we can't help ourselves. We're human. We have no choice but to hate. That is a lie. Unfortunately, it is a lie many people believe. They believe this lie in order to excuse their hatred. After all, if we can't help but hate, if hate is a feeling we simply cannot help, then hatred is never our fault, is it?

But we can help it. Hatred is a choice. We choose to hate, just as we choose to love. Oh, I know, there are people out there who believe love isn't a choice, that love is primarily an emotion, a feeling, a stirring in the loins. These are the same people who stay married for six moths and then divorce. These are the people who love the idea of love but seems unable to stay in it. Love is a matter of the will, something we decide to do. Love is a choice.

And so is hatred. Hatred is something we decide to do. We can hate our ex-spouse, but we don't have to. It is our choice. We can hate Muslims, but we don't have to. It is our choice. We can hate black people or yellow people, but we don't have to. It is our choice. We can hate homosexuals, but we don't have to. It is our choice. Hatred, like love, is a choice.

Hatred is the refuge of those who won't grow up. Haters are moral infants, perennial children, tantrum throwers who haven't gotten their way. When my six year old is that way, I can understand it. I don't excuse it, but I understand. Then I work hard to make sure he doesn't stay that way. I let him know in no uncertain terms that hatred is not acceptable. It is scary to think how many people turn their children loose in the world without ever teaching them that.

If there is a time to hate, as Ecclesiates suggests, it is when we are children, when we don't know any better , when we think hate is something we can't help. The apostle Paul knew this. In 1 Corinthians 13, he observed that when he was a child, he spoke, thought, and reasoned as a child. But when he grew up, he put aside childish ways. Since Paul was writing about love, I think the childish thing he laid aside was hate. When Paul laid aside hate, when Paul grew up, he was able to appreciate the transforming power of love.

This is what Carolyn Kellum was trying to teach me when I first became a Christian. But I was too busy thinking about teenage girls to pay her any mind. This was back in the days when I spoke, thought and reasoned as a child. Now I'm trying to set aside my childish ways. It isn't easy. Spiritual maturity is a lifelong process, accomplished one choice at a time.

Sometimes, after reading newspaper accounts of killings far and near, I lay aside the paper, close my eyes, and dream of a world where the only thing people hate is hatred.

Quakers for Travel Justice - could it be a Quaker concept? By Elizabeth Dooley

About fifteen years ago, I determined to live a life where my carbon footprint was as low as possible, so I left Auckland for Nelson with the intention of living without a car. This is also the time I joined the Nelson Meeting of the Society of Friends, Aotearoa (Quakers).

I bought myself a bike and cycled my way around town. I even managed to cycle out to St Arnaud a few times. In 2008, it was a breeze. Car drivers gave me a wide berth and congestion was just something that happened in Auckland.

To my surprise, over the next few years, cycling became more precarious with the increase in angle-parking and the growth of SUVs. I discovered (the hard way) that car drivers will knock you off your bike on a roundabout and say (inevitably) "I didn't see you". I discovered (just as painfully), that car drivers will fling their car door open just as you are cycling by. People were reversing their angle-parked cars without being able to see what they were reversing into, because they found themselves parked beside an SUV, obstructing their view.

I felt unsafe on Nile Street and Trafalgar Street – trying to spot drivers in parallel parking spaces or some sign of movement in the angle-parked vehicles. I kept well away from the backs of these vehicles, but this angered some people driving their cars and keen to pass me without slowing down. Loud horns, abuse – sometimes I found myself shaking.

I decided to walk everywhere I possibly could – its only half an hour to the City Centre. That was when I discovered that walking around town is not such a pleasant pastime. Empty private vehicles parked on the side of the road obscure my view when trying to cross the road. There are very few pedestrian crossings and they are not conveniently sited. These are public streets I’m talking about – not highways. Public streets are our legal ‘commons’. They belong to us all – tall, short, sighted, blind, lame, athletic. Please take a moment to imagine those streets free of parked cars on both sides of the street. There’s twice the room and we can see!

By the way ‘street’ originally meant ‘the space between buildings’ - in other words, the space where we say kia ora, notice a pretty dress or a crying child; all human life is there and when you drive everywhere – you don’t meet them. You become somewhat alienated from your fellow citizens.

Of course, things are worse for my wheelchair-using fellow citizens. There are very few footpaths with a slope to allow wheelchair users to cross the street and mount the footpath in front of the shop or office they are heading for. Being positioned so low, they have not a chance of seeing past the parked cars. Of course the drivers of the moving cars - mostly 50kph – are unaware of the effect they are having on the people trying to navigate the city without a car. You and I will never know how many people stay home, or continue to drive into town because they feel unsafe. And yet they are lonely and would love to wander along meeting and greeting, and resting when they need to, on a convenient seat.

To understand what happened – here is a link to a great analysis around ‘traffic language’: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/bike-blog/2022/aug/31/how-car-culture-colonised-our-thinking-and-our-language.

A few years ago I joined a sustainable transport activist group called Nelsust (they prevented the Southern Link poisoning the air in Victory 20 years ago). They work hard to lobby central and local government about the joys of active travel – the value to the health and wellbeing of all of us. Of course, to realise what is sometimes called ‘the 15 minute Paradise’ - it needs to be safe for all, fair for all. There’s heaps of room for cycling on our roads – it just happens to be filled up with empty private vehicles right now. There is an opportunity for my friend Ben (Downs Syndrome and a little deaf) to cross the road safely because cars have slowed down and the streets he needs to cross (Vanguard and St. Vincent’s) have proper crossings with a button he can press so that he hears the traffic stop before stepping out.

Nelson City and Tasman District Councils have taken on board much of what we have been saying and the new travel and parking strategies go some way towards a sustainable future. The outcome of the revolution I call "Travel Justice" would be quieter public spaces, safe walking and cycling for everyone, independent children making their way safely to school and to play with their friends, wheelchair users and other disabled folk being consulted and provided for, less pollution, less toxic air and most of all, less fear and anxiety and a growing sense of community.

Last May, Nelsust held a ‘Travel Justice’ rally and everyone brought information about the place they felt least safe in Nelson. We took this to the Council. We hope to rally again this May and perhaps find improvements are just around a (highly visible) corner...

A better life and lower Greenhouse Gases are just around that corner.

What is true? How can you tell? Jan Marsh reviews recent Quaker writings on these questions

Classic Quaker View. Reprinted

The two Quaker publications I'm reviewing originate in the UK against a backdrop of Brexit and Covid, occasions of great social change accompanied by misinformation and disinformation. They challenge us to form our own understanding of what Truth is.

In Friends Quarterly (i) , four Friends reflect on truth from their professional and philosophical perspectives. They define 'truth decay' as being characterised by:

• increasing disagreement about facts

• blurring the line between opinion and fact

• the increasing volume, and resulting influence, of opinion over fact

• declining trust in formerly respected sources of facts.

John Lampen writes about “doing truth" (John 3:21). He gives an example of founder George Fox refusing the King's pardon in order to be freed from prison in the 1650s for challenging the state church because it would 'dishonour truth' to be pardoned when he had not committed a crime. There are other examples of early Quakers acting 'in truth' as well as speaking truth. One such is Friends' well-known business ethics.

The issue of Truth is an urgent one. Is a post-truth society in fact a culture of lying? We all have our own inner guide, so we have the capacity to recognise truth, and we can choose to act with integrity. What collective action are we being called upon to do today to show the importance of Truth?

Jane Dawson takes her starting point from Keats: 'Beauty is truth, truth beauty.' Keats implies it is beyond mere mortals to know Truth. She looks at the rise of social media and disinformation but demystifies the medium by pointing out that we have always been guided by our emotions and a tendency to only believe sources we agree with. A diet of tabloid newspapers in Britain has long been a source of biased information. The same could be said of other publications.

Social media simply speed up the process. Changes in the law eventually become changes in moral and cultural truths – and, I would say, vice versa. She comments that 'England is deeply scarred by the Norman Conquest' i.e., creating a definition of England that served the conquerors and impoverished the people already living there - she describes a process familiar to those of us who reflect on colonisation in Aotearoa. Our myths, stories and language give us a framework for truth, and she questions whether, outside these contexts, we can ever really know an objective truth.

Bob Ward draws on his experience as a scientist and a prison minister. While scientific evidence may reveal the truth in a given context, methods and knowledge evolve and change. On the other hand, spin and metaphor might disguise the truth. To get at the truth, Ward recommends the procedures of mediation: careful listening, respect for different views, fairness, acknowledging just criticism and seeking positive outcomes. 'Facts' may be established but their interpretation depends on context. We achieve social coherence by agreeing to shared 'truths' but outside of mathematics, the absolute is elusive.

David Brown brings Carl Jung's map of psychological functions to bear on the subject. We may experience truth through our Spiritual, Thinking, Intuition, Feeling and Sensation functions. They can be used as tools to assess both absolute and relative Truth. There will be those who draw more heavily on one function than another. Combined perceptions, i.e. collective discernment, will give a more complete view. In short, we can ask questions such as 'Does it sound right?' 'Does it feel right?' 'Is it rational?', 'Is it moral?', or 'Is there more than meets the eye?' We need to align our experience of inner truth with our perception of truth in the world.

Thomas Penny's Swarthmore Lecture (ii) covers different territory. A journalist and political correspondent of wide experience, he takes the reader on a step-by-step journey around the subject of truth, beginning with the 'argument, games and chicanery' over Britain leaving the European Union, followed by the confusion over the pandemic. Using biblical and Quaker writings, Penny guides us through the ethics of truth and conflict resolution.

A point Penny makes, as does Jane Dawson in the Friends Quarterly, is that misinformation is not only the invention of modern social media. Penny takes us back to the turbulent times of the mid-seventeenth century, when the Religious Society of Friends was emerging. The new social medium then was the printed tract. Wider access to printing encouraged literacy and reduced hierarchies. In the ferment of ideas as the civil war raged, propaganda and wild invention circulated through newssheets, ballads and tracts which crossed the country with stories of outlandish supernatural events, grossly exaggerated massacres and lies about all parties. The church had lost its grip as the main source of dogma and for a time a 'post-truth' era reigned.

As Quakers emerged in the 1650s, they too were slandered and vilified. From these roots, it is not surprising that Friends developed a strong concern for truth and in time their commitment to being truthful in word and action allowed them to thrive and become trusted. However, Penny calls out a certain amount of Quaker spin. For example, in spite of the earnestly stated peace testimony, there were many Quakers in the army.

Quakers felt themselves to be 'Watchmen' as described by Ezekiel, that is, those who are called on to monitor their community and call out behaviour which jeopardises another's spiritual well-being. John Woolman is a shining example of this, living his life with the utmost integrity and writing of the difficulties of accepting a Friend's hospitality and yet challenging their failings as he felt he must. That he did not spare himself might have made his challenges a little easier to bear.

As people take strong positions, they become more polarised, and divisions develop in society. So where does truth lie? Penny says that early Friends found truth 'at the meeting point of facts and lived experience.' I found that phrase spoke to me. When Fox concluded that the answer to his search was in the importance of a direct relationship with Christ, it was the culmination of years of study, searching and experience. His assertion 'This I knew experimentally' was no simple flash of intuition. Quakers value both the experience of the individual life and the group discernment in which conclusions are tested. This is very like the scientific method in which results are never certain and are always open to new information, or 'new light' as we might say. Doubt is not the absence of truth but a creative force inspiring further searching.

Penny gives a moving example of his own in which he witnessed the police shooting of a terror suspect who had driven a car into pedestrians on Westminster bridge. He shows in generous detail how he went through stages of 'truth': what he saw, how he and a colleague made sense of it to share the information as journalists, how he gave a minute step-by-step account to the police and how, on his way home after the attack, he cried in the bus as he reached the emotional truth of the event. He followed up with several sessions of counselling to examine the experience and its effect on him. This layered approach shows how complex even the truth of an eyewitness really can be.

So how do we assess truth? Drawing on his journalism skills, Penny encourages us to be open to different perspectives and to interrogate our sources with key questions: 'Who is telling me this? Why are they telling me this? What is their evidence? What do they hope to gain? Who is their audience? What do they want the reader or listener to think? Who's paying them? And so on.'

Even so, opinions can become polarised, especially as people trust entirely different sources of information. Penny urges us to find space to communicate, space within ourselves and in our meetings, in the way that QUNO (Quaker United Nations Office) offers space for delegates to quietly talk with each other.

The title of the lecture comes from hearing a farmer say that as the weather grew harsh, she would bring her animals down to 'kinder ground.' Penny encourages us to find a respectful, compassionate place where we can meet with and listen kindly to those whose views we do not agree with.

I found both these booklets thoughtful and helpful in a time of overwhelming amounts of information and conflicting opinions. They are also interesting and well-written. I encourage Friends to seek them out and read them.

i. The Friends Quarterly Issue number four 2021: Truth decay. Authors: John Lampen, Jane Dawson, Bob Ward & David Brown

ii. Swarthmore Lecture 2021, Kinder Ground: Creating space for truth. Thomas Penny.

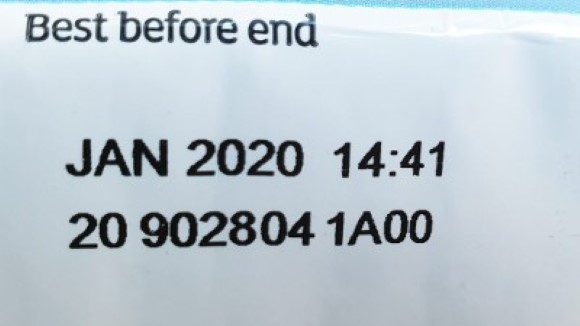

Is the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) past its use by date? By Jan Marsh

It is almost impossible to imagine the conditions in seventeenth century England that gave rise to the Society of Friends. The wearying years of civil war had created a yearning for peace. Religious conformity was savagely enforced by torture and brutal executions as the country swerved from Catholic to Protestant and back at the whim of the rulers. A mere two generations prior, reading the Bible in English was punished by death because of the threat it posed to the power of the priests, who were exposed as ignorant and duplicitous.

Out of this harsh crucible came the vision of George Fox and other seekers, for a more equal, just and peaceful life. Sincere, spiritually minded people were beginning to find their own path as they could read the teachings of Jesus first-hand and learn to have confidence in their own inner light. The development of the testimonies makes absolute sense in this context and time when there was a radical re-visioning of a more grassroots, loving way of life.

Today, the values the testimonies encapsulate are part of everyday goals of education and enshrined in bills of rights. Quakers have been part of many international movements for peace and justice – Greenpeace, Amnesty International, other human rights and climate movements; organisations which are widely respected and have diverse membership now. Has the Quaker leaven done its job? Is it no longer needed?

As I look around the meeting room on a Sunday morning, most of the bowed heads are silver-haired. An ageing membership is no doubt true of most Christian denominations. As I sit, enjoying the sunshine coming through the windows and the flowers on the table, I ponder what I would miss if Quakers ceased to exist. I would miss the hour of silent worship on a Sunday morning which settles and grounds me and is different from the silence of meditating or the quiet hours of living alone.

I would miss the personal history bound up with Friends since I first attended Mt Eden Meeting with my two pre-schoolers nearly 40 years ago. I remember how delighted I was with the warm welcome, the mix of age groups, family camps at Waiheke and the feeling of excitement that rose in me as I came to Meeting each Sunday – what will happen in this next hour?

I would miss the more than 370 years of Quaker history, our forebears with their courage and insights which have been shared down the years in Quaker Faith and Practice. I would miss Quaker literature: the thoughtful essays and books which develop a unique spiritual process, and the occasional fiction. I would miss my Friends who I see each Sunday and those from around the country who visit or get in touch by email.

To my mind, the essence of Quakerism lies in the name: Religious Society of Friends. Our purpose is to be a community which gives love and support to our members as we find our way through the trials and joys of life. For this we draw on our values, our inner Light and the insights of other Friends. It is important to remember that without this loving community we are no longer unique: there are many secular organisations which embody the values we profess.

Kindness and community are essential, or as Isaac Pennington put it: Our life is love, and peace, and tenderness: and bearing one with another, and forgiving one another, and not laying accusations against another; but praying one for another and helping one another up with a tender hand. (1667)

Classic Quaker View: Thoughts on Sustainability by Lawrence Carter

First, I want to say that, in questions about the physical world we can never do better than take the results of peer reviewed science. Scientific knowledge is based on theories, which are tested by careful experiments, and the results published in peer-reviewed journals. To get to publication, a paper must endure the severest scrutiny by other scientists. Once published, it represents our best possible knowledge at that time. Over time, new theories might emerge, which could fit the observed facts better. These are subject to the same rigorous process, which decides whether these new ideas are better than the old, or not. The point is that, at any given time, peer-reviewed science gives us our very best knowledge: we can't do better!

I say this because sometimes people who don't like what science is telling them, will try to argue against it by using a quasi-scientific approach, using perhaps a scientific guru to strengthen their claim. However, such an approach is invariably found to have avoided the peer review necessary for credibility.

We seem to be in a period when multiple environmental crises are happening. Overpopulation, loss of forests, pollution of air, land and sea, decline of resources we use, loss of species, ocean acidification, the list goes on. But the one that focuses my attention the most, because of its far-reaching consequences, is climate change. In simplified summary, the problem is this: increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, since the start of the industrial revolution, causes an increase in global warming due to the so-called greenhouse effect; this warming causes polar ice to melt, and this extra, warmer water causes sea-level rise. This is likely to cause flooding problems for our cities, most of which are built on low-lying coastal margins. Nelson City Council is basing their planning on an expected sea-level rise of about one metre by 2100, which is realistic. This is the problem of climate change as outlined by our scientists, but some people in power, and especially those connected to the fossil fuel industries, refuse in public to believe these scientific truths. So we all have a problem that is even bigger than it needs to be!

I guess these concerns have come about through reading about the issues, but mostly through my association with Engineers for Social Responsibility (ESR), a group of professional engineers who accept that the professional engineer's duty extends beyond the client, to include people generally and the environment we all live in. Over the last four or so years ESR has carried out a programme of education about climate change, sponsoring peer-reviewed information sheets on various aspects of the problem, and publishing these both in print and on our website esr.org.nz. I have helped with this, and so become aware of some of the issues, especially with regard to sea-level rise.

While these concerns and actions have not come about directly through contact with Quakers, I believe they fit pretty well with Quaker values. Quakers value people. In fact each person is held to be of infinite value. Quaker values are embodied in the acronym SPICE: simplicity, peace, integrity, community, and equality; to which has been added stewardship, or sustainability, so SPICES. Basically, it's about caring for people and the world in which we live. Quakers try to take practical steps in their lives to improve the world.

How can we live more sustainably? We all need to put a lot less carbon into the air. If we make a big effort to do this, we can take the edge off the worst effects of global warming. We need to live simple, low energy lives. Of course that's easy to say, and not so easy to do! For myself, I need to work on emitting less carbon when I travel. I have a small, low emission car, but it still burns petrol. I would really like to switch to an electric vehicle, and I need a bike too.

The real progress will be made when we realise that decisions have to be made at government level to curb our emissions. In New Zealand this hasn't happened yet - our emissions per head are amongst the highest in the world, which is really shameful. We desperately need political leadership to take the hard decisions. We in our turn need to be prepared to support our politicians in taking these politically-risky decisions, which may in the short term lower our quality of life.

What is true? How can you tell? Jan Marsh reviews recent Quaker writings on these questions

The two Quaker publications I'm reviewing originate in the UK against a backdrop of Brexit and Covid, occasions of great social change accompanied by misinformation and disinformation. They challenge us to form our own understanding of what Truth is.

In Friends Quarterly (i) , four Friends reflect on truth from their professional and philosophical perspectives. They define 'truth decay' as being characterised by:

• increasing disagreement about facts

• blurring the line between opinion and fact

• the increasing volume, and resulting influence, of opinion over fact

• declining trust in formerly respected sources of facts.

John Lampen writes about “doing truth" (John 3:21). He gives an example of founder George Fox refusing the King's pardon in order to be freed from prison in the 1650s for challenging the state church because it would 'dishonour truth' to be pardoned when he had not committed a crime. There are other examples of early Quakers acting 'in truth' as well as speaking truth. One such is Friends' well-known business ethics.

The issue of Truth is an urgent one. Is a post-truth society in fact a culture of lying? We all have our own inner guide, so we have the capacity to recognise truth, and we can choose to act with integrity. What collective action are we being called upon to do today to show the importance of Truth?

Jane Dawson takes her starting point from Keats: 'Beauty is truth, truth beauty.' Keats implies it is beyond mere mortals to know Truth. She looks at the rise of social media and disinformation but demystifies the medium by pointing out that we have always been guided by our emotions and a tendency to only believe sources we agree with. A diet of tabloid newspapers in Britain has long been a source of biased information. The same could be said of other publications.

Social media simply speed up the process. Changes in the law eventually become changes in moral and cultural truths – and, I would say, vice versa. She comments that 'England is deeply scarred by the Norman Conquest' i.e., creating a definition of England that served the conquerors and impoverished the people already living there - she describes a process familiar to those of us who reflect on colonisation in Aotearoa. Our myths, stories and language give us a framework for truth, and she questions whether, outside these contexts, we can ever really know an objective truth.

Bob Ward draws on his experience as a scientist and a prison minister. While scientific evidence may reveal the truth in a given context, methods and knowledge evolve and change. On the other hand, spin and metaphor might disguise the truth. To get at the truth, Ward recommends the procedures of mediation: careful listening, respect for different views, fairness, acknowledging just criticism and seeking positive outcomes. 'Facts' may be established but their interpretation depends on context. We achieve social coherence by agreeing to shared 'truths' but outside of mathematics, the absolute is elusive.

David Brown brings Carl Jung's map of psychological functions to bear on the subject. We may experience truth through our Spiritual, Thinking, Intuition, Feeling and Sensation functions. They can be used as tools to assess both absolute and relative Truth. There will be those who draw more heavily on one function than another. Combined perceptions, i.e. collective discernment, will give a more complete view. In short, we can ask questions such as 'Does it sound right?' 'Does it feel right?' 'Is it rational?', 'Is it moral?', or 'Is there more than meets the eye?' We need to align our experience of inner truth with our perception of truth in the world.

Thomas Penny's Swarthmore Lecture (ii) covers different territory. A journalist and political correspondent of wide experience, he takes the reader on a step-by-step journey around the subject of truth, beginning with the 'argument, games and chicanery' over Britain leaving the European Union, followed by the confusion over the pandemic. Using biblical and Quaker writings, Penny guides us through the ethics of truth and conflict resolution.

A point Penny makes, as does Jane Dawson in the Friends Quarterly, is that misinformation is not only the invention of modern social media. Penny takes us back to the turbulent times of the mid-seventeenth century, when the Religious Society of Friends was emerging. The new social medium then was the printed tract. Wider access to printing encouraged literacy and reduced hierarchies. In the ferment of ideas as the civil war raged, propaganda and wild invention circulated through newssheets, ballads and tracts which crossed the country with stories of outlandish supernatural events, grossly exaggerated massacres and lies about all parties. The church had lost its grip as the main source of dogma and for a time a 'post-truth' era reigned.

As Quakers emerged in the 1650s, they too were slandered and vilified. From these roots, it is not surprising that Friends developed a strong concern for truth and in time their commitment to being truthful in word and action allowed them to thrive and become trusted. However, Penny calls out a certain amount of Quaker spin. For example, in spite of the earnestly stated peace testimony, there were many Quakers in the army.

Quakers felt themselves to be 'Watchmen' as described by Ezekiel, that is, those who are called on to monitor their community and call out behaviour which jeopardises another's spiritual well-being. John Woolman is a shining example of this, living his life with the utmost integrity and writing of the difficulties of accepting a Friend's hospitality and yet challenging their failings as he felt he must. That he did not spare himself might have made his challenges a little easier to bear.

As people take strong positions, they become more polarised, and divisions develop in society. So where does truth lie? Penny says that early Friends found truth 'at the meeting point of facts and lived experience.' I found that phrase spoke to me. When Fox concluded that the answer to his search was in the importance of a direct relationship with Christ, it was the culmination of years of study, searching and experience. His assertion 'This I knew experimentally' was no simple flash of intuition. Quakers value both the experience of the individual life and the group discernment in which conclusions are tested. This is very like the scientific method in which results are never certain and are always open to new information, or 'new light' as we might say. Doubt is not the absence of truth but a creative force inspiring further searching.

Penny gives a moving example of his own in which he witnessed the police shooting of a terror suspect who had driven a car into pedestrians on Westminster bridge. He shows in generous detail how he went through stages of 'truth': what he saw, how he and a colleague made sense of it to share the information as journalists, how he gave a minute step-by-step account to the police and how, on his way home after the attack, he cried in the bus as he reached the emotional truth of the event. He followed up with several sessions of counselling to examine the experience and its effect on him. This layered approach shows how complex even the truth of an eyewitness really can be.

So how do we assess truth? Drawing on his journalism skills, Penny encourages us to be open to different perspectives and to interrogate our sources with key questions: 'Who is telling me this? Why are they telling me this? What is their evidence? What do they hope to gain? Who is their audience? What do they want the reader or listener to think? Who's paying them? And so on.'

Even so, opinions can become polarised, especially as people trust entirely different sources of information. Penny urges us to find space to communicate, space within ourselves and in our meetings, in the way that QUNO (Quaker United Nations Office) offers space for delegates to quietly talk with each other.

The title of the lecture comes from hearing a farmer say that as the weather grew harsh, she would bring her animals down to 'kinder ground.' Penny encourages us to find a respectful, compassionate place where we can meet with and listen kindly to those whose views we do not agree with.

I found both these booklets thoughtful and helpful in a time of overwhelming amounts of information and conflicting opinions. They are also interesting and well-written. I encourage Friends to seek them out and read them.

i. The Friends Quarterly Issue number four 2021: Truth decay. Authors: John Lampen, Jane Dawson, Bob Ward & David Brown

ii. Swarthmore Lecture 2021, Kinder Ground: Creating space for truth. Thomas Penny.

Can we stay friends? By Jan Marsh

In Thomas Kenneally's book 'Flying Hero Class' there's a line that has stayed in my mind over the years. The situation is the hijacking of a passenger plane. A group of passengers has been singled out by the hijackers to show an example to the others. Stripped to their underwear and humiliated, they've been shoved into the hold where they are cold and without toilet facilities, increasingly filthy. They are trying to make a plan to overwhelm the hijackers and one of the focus characters says, 'The chances are most of us will survive this. Let's not do anything we can't live with afterwards.'

Covid has changed our way of life and caused governments to impose restrictions which are usually reserved for times of war. Even though we will soon reach over 90% of New Zealanders fully vaccinated, so it must be a small minority who object, vaccination is causing rifts. In my own family there are those who consider the vaccination and other restrictions unwarranted, even dangerous, and those who are immune-compromised and keen for protection. The same is true among my friends and other social groups and in some cases, animosity is rising.

As for me, I'm fully vaccinated because it seems the right thing to do for the good of the community: to lessen the grip the virus has on our way of life, to make sure our already stretched health system is not over-burdened and to reassure friends and family who are concerned for my health or their own. I don't often get sick so I'm not particularly afraid of the virus for myself but as I'm approaching 70, perhaps I should be a little concerned. A recent bout of a (different) respiratory virus took longer than usual to shake off, showing I'm perhaps not as resilient as I was 20 years ago.

I'm also not afraid of vaccines. I've had a few in my time: the first I remember is lining up at school for the polio vaccine in the form of drops on my tongue. I don't recall any children being exempted by their parents - the memory of the terrible effects of polio was still vivid. My own grandfather was affected and had his withered leg amputated, a source of fascination to us kids.

When I set out on my OE I had to have a number of vaccines for diseases such as cholera, typhoid, yellow fever, and I had to carry a card which recorded that I had had those. The card was checked at every border, and I would not have been allowed to continue without it. I can recall one unscrupulous guard at the Turkish border trying to tell me I needed more injections and expecting to be paid off to let me through, but I stood my ground on both scores and after some delay went on my way.

Most recently, prior to Covid, my daughter asked me to make sure my pertussis vaccination was up to date before meeting my new granddaughter. I saw my doctor about that and got a shot with a tetanus booster thrown in. I wouldn't have sought those out but they did me no harm, reassured my daughter and all is well. In no case did I have any idea what was in the vaccines – disease-defeating stuff, I assumed. I trusted that my doctor would have my best interests in mind when she offered what was needed.

My main thought about the present situation is that the greatest risk to most of us is not to our health through having the vaccine or even through getting Covid, but to our relationships by having conflict over it. Can we hear each other's points of view without having to shout them down? Can we respect each other's choices and do whatever it takes to help each other feel safe? That might mean wearing a mask when it doesn't seem really necessary, staying home when we have a cough or keeping our distance in some circumstances. If we love our family and friends, of course we want them to feel safe. Perhaps we want to argue with them in order to make sure they are doing the best for their health, but we each have different views about what's best. Can we respect that?

Most of us will survive this. Let's make sure we can look each other in the eye when it's over and still be friends.

Classic Quaker View, from the archives: Spring again. By Jan Marsh

>

photo by Yoksel Zok Unsplash

Once again, the early birds are waking me with their calls. I can feel the change happening as I'm more ready to get up these mornings and less likely to huddle under the duvets (yes, two in winter!) resisting the sharp bite of a frosty morning.

A pair of tuis were in the pear tree this afternoon, glossy and fat, diving and flapping their wings at each other. Were they courting or fighting? Hard to tell. A simple tune rings out over and over as they fly from one treetop to another around my garden. The hellebores are flowering thickly under the plum tree, their shades of mauve and green dusted with little white petals which drift down from the tree. The daffodils are beginning to droop and the crocuses have disappeared back into the earth after briefly popping their heads above the surface.

Soon there'll be more blossom – the cherry, the pear – but this year the Granny Smith apple tree is gone. It fell down at Easter, the ground too sodden to hold its roots. I've cooked and frozen the last of the apples which I had stored in the shed. That's the second apple tree to die in that patch of lawn so I won't plant another there. A magnolia might be nice – I'm admiring their display all over town just now. It's a short but glorious shout out to spring and makes me think of Walt Whitman's Louisiana oak 'uttering joyous leaves of dark green'.

The spring has given me a boost to get on with some chores. The concrete has been cleaned up and I'll seal it to keep the moss at bay; the house too is washed and shiny but the windows are streaky. Small repairs inside and out have been done but there's some paintwork to touch up when we get another fine day. It's all part of loving my home.

It also feels as though I'm tidying it up to a point where I could leave for a while. Where to, I wonder? Maybe this is just the restlessness of spring and when summer comes I won't want to be anywhere else but here in my home among my friends.

I Saw in Louisiana A Live-Oak Growing

By Walt Whitman

I saw in Louisiana a live-oak growing,

All alone stood it and the moss hung down from the branches,

Without any companion it grew there uttering joyous leaves of dark green,

And its look, rude, unbending, lusty, made me think of myself,

But I wonder’d how it could utter joyous leaves standing alone there without its friend near, for I knew I could not,

And I broke off a twig with a certain number of leaves upon it, and twined around it a little moss,

And brought it away, and I have placed it in sight in my room,

It is not needed to remind me as of my own dear friends,

(For I believe lately I think of little else than of them,)

Yet it remains to me a curious token, it makes me think of manly love;

For all that, and though the live-oak glistens there in Louisiana solitary in a wide flat space,

Uttering joyous leaves all its life without a friend a lover near,

I know very well I could not.

Source: Leaves of Grass (1891-2) (1892)

Whats up with Rocket Lab? Rocket Lab Monitor and Auckland Peace Action have the answer

The following information was published by Auckland Peace Action to support their demonstration against Rocket Lab on June 21st 2021. Supporters of APA gathered outside the Auckland Headquarters of Rocket Lab to highlight concerns about NZ being entangled in the US Military Star Wars programme. It is reproduced here to help widen the spread of this vital information, with thanks from Quakers in Nelson to Rocket Lab Monitor and APA for bringing it together.

Who owns Rocket Lab? Rocket Lab was founded in New Zealand in 2006 by Peter Beck and Mark Rocket. Early investors included the likes of Stephen Tindall's K1W1 Fund and ACC along with US venture capital funds and more recently the world's largest weapons manufacturer Lockhead Martin. Rocket Lab is now owned by Rocket Lab USA and plans to list on the NASDAQ with a value of over $4 billion.

Who does Rocket Lab serve? Rocket Lab customers include weapons dealers and military clients, mostly from the US but also Germany and Australia.

Weapons targeting systems deployed by Rocket Lab like the Gunsmoke - J payload in March 2021 for the US Army can control both conventional and nucleur weapons. Intelligence gathering technology deployed by Rocket Lab serves US military, economic and political interests.

What do Locals think? Rocket Lab's launch site at Mahia received consents from Wairoa District Council in just nine days, with no public consultation on the untested claim that local Maori supported the proposal. Mahia residents, including veteran peace activist Pauline Tangoroa, have made it clear that Rocket Lab representatives including Peter Beck misled locals to get support from Mahia residents. Rocket Lab negotiated a long term lease for the launch site with only the trustees of the Maori land block the site is based on. There was no other consultation with other owners of the land. Many locals are now strongly opposed to the Rocket Lab base at Mahia.

What is the Government doing? Cabinet agreed on principles which prohibit payloads that may damage or destroy the environment or other infrastructure but is silent on payloads of technology designed to damage or destroy people.

New Zealand should push the US to support the UN Treaty for Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS) which to date has been blocked by the US but supported by the majority of countries at the United Nations.

What can we do? Stay informed: find out more by doing your own research and have a look at www.rocketlabmonitor.com

Share information: talk to your family and friends about whether they think New Zealand should be permitting military payloads.

Contact politicians: >write to PM Jacinda Adern, Minister for Economic and Regional Development Sturat Nash, Minister for Disarmament and Arms Control Phil Twyford, and/or Minister of Foreigh Affairs Nanaia Mahuta to ask them to explain why they allow weapons systems to be launched from NZ for foreign companies and military agencies.

PM: j.adern@ministers.govt.nz s.nash@ministers.govt.nz p.twyford@ministers.govt.nz n.mahuta@ministers.govet.nz

Get Involved: Rocket Lab Monitor - www.rocketlabmonitor.com collects information about Rocket Lab, the New Zealand Space Agency and relevant legislation and the activities of Rocket Lab clients.

Space for Peace Aotearoa - spaceforpeace@protonmail.com

Auckland Peace Action - aucklandpeaceaction.wordpress.com

Global Network against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space - www.space4peace.org

Space for Peace Petition - This petition asks the Government to refuse consent for Space industry activities which contribute to organised international warfare and the weaponisation of Space: https://ouractionstation.org.nz/petitions/space-for-peace-3